It was the richest, most avant-garde, secular country of the entire Middle East. One of the smallest nations of the world held the hearts of people from the region and beyond. Its cosmopolitan heyday lasted roughly from the mid-50s to 1975.

It was the emblem of liberalism, of how – at least on the surface – differences can unite a coexisting variegated population: Muslims Sunni and Muslim Shi’ite, Christians.

All together in that tiny land of mountains and Mediterranean Sea, that handkerchief on planet earth that was so unique it allowed you to go skiing in the morning and swimming in the afternoon. Everything seemed easy, reachable and possible in Lebanon, starting from happiness.

On the surface, it mattered little if it was France, the colonizing power up to 1943, who drew Lebanon’s borders, if starting from then the country was ruled by a sectarian elite, if factions of self-interest always prevailed ahead of state and nation and if the idea of a nation was still embryonic.

The intentions were good: at the founding of Lebanon, under the National Pact, it was agreed the President had to be a Christian Maronite, the Prime Minister a Sunni, the Speaker of Parliament a Shi’ite Muslim. The quota of democracy.

In 1952 Lebanese women gained the right to vote and, the year after, Parliament drafted one of the first anti-corruption laws of its kind. Lebanon was ahead.

Tourism boomed, both from the Arab World and from afar. The jet-set had chosen Beirut to holiday and be seen, jet-ski and indulge.

Brigitte Bardot, Peter O’ Toole, ElizabethTaylor and Richard Burton, Omar Shariff, King Farouk of Egypt were habitués of the iconic St. George’s Hotel; Casino du Liban hosted Miss Europe beauty pageant (1964) and was the stage where Duke Ellington and Jacques Brel performed.

Postcards from Lebanon made everyone dream.

Middle Eastern companies were transferring their headquarters to Lebanon, Beirut was the financial and trade centre of the entire region, its harbor known for hosting cruise liners (see the Queen Elizabeth II) while the American University was the debating society of the new thinkers.

That Mediterranean appeal with the Near Orient flare were the perfect alchemy. Yet, it was glamorous, but there was no national unity, still.

It was affluent, but not for everyone: poverty, out of Beirut, was spread. It was fashionable and avant-garde, but beneath the surface discontent was palpable, deriving from sectarian politics.

Lebanon – like no other country in the world – was continuing to bear the shockwave of the creation of the State of Israel (1948) which had sent 100,000 Palestinian refugees over the border.

It was a foretold catastrophe and it started in 1975.

The war, a prolonged agony, lasted up to 1990. Over fifteen years of numerous internal and external contenders, alliances and frequent reversals of alliances, of massacres. Endless. It became one of the most difficult conflicts to report and analyze, fought from building to building, door to door, window to window, breath to breath. It was the war of the neighbourhoods, streets, barricades and barrage of atrocities and explosive devices. It was the war that generated subconflicts, claimed the life of at least 120,000 people and swallowed 17,000 through forced disappearances.

It was chaos, with Syria dreaming to place Lebanon under the project of a ‘Greater Syria’ and Israel intending to oppose the PLO (Palestinian Liberation Front) militiamen creating a security zone under their control.

At the root, though, it was pain. Immeasurable pain, still felt today.

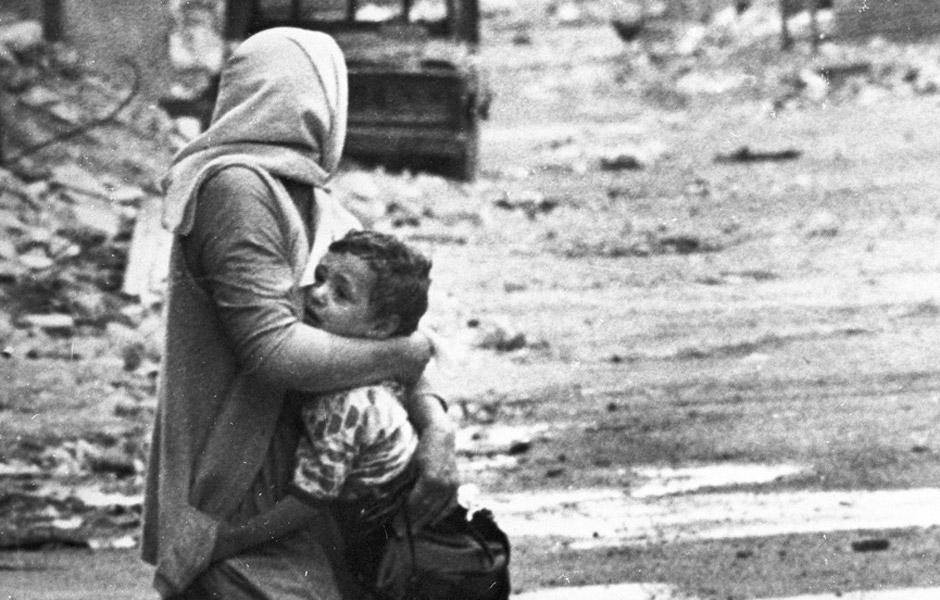

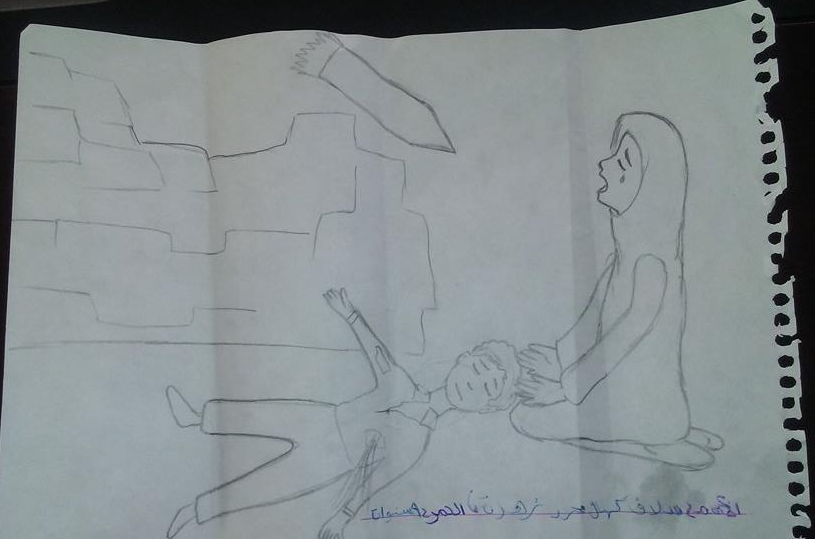

One night, I happened to watch some footage from the War of the Camps, a sub-conflict within the 1984–89 phase of the Lebanese civil war in which Palestinian refugee camps were besieged.

Of all the horror I swallowed, I could not refrain hiccups and tears when the images moved to a wounded child, on a ‘hospital’ bed.

There was nothing human in that scene.

A grown up was telling the young boy to be strong and resist.

The child asked how could he resist and the grownup replied “Pray, pray to God”

And so the boy did.

Laying in his trauma, his tattered bloodied clothes, the boy uttered:

“Dear God, protect my father. Dear God, protect my mother”.

Amid an ocean of obscenities, a tiny clean island.

Amid soul-corrupting hate and inhumanity, a quiet utterance of human soul.

This is surely a purity that should make all hearts, human and godly, weep.

The machines of hate are never silenced.

But one candle then, and many like it now, flicker their fragile human light against the blackest of blacks.

We can only trust and hope, that hope is never lost.

photo: A Palestinian refugee and her child caught in sniper fire during the War of Camps. Author: unknown