Mujahideen, the Taliban, North American invasion of 2001, the struggle for democracy (whose democracy? Which democracy?), through the eyes, scars on skin and words of the actors on the ground.

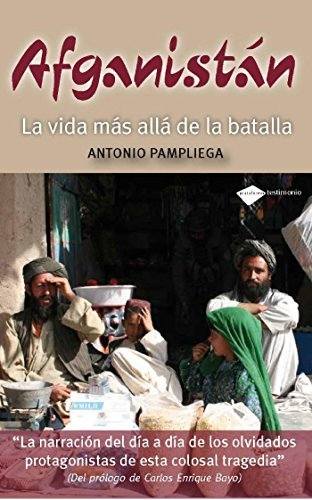

Antonio Pampliega‘s book Afganistan Mas Allá de La Batalla (Testimonio) had the intent to humanize the inhumanity of war and, specifically, the endless state of wars in Afghanistan, a country so torn that newsrooms can no longer handle truth.

Nobody cares any longer.

Nobody cared and cares of Sayid, barely four months old who died quietly, in a hospital bed where there are no medicines, where machinery donated by NGOs could not benefit from maintenance or the luxury of top-notch spare parts.

Nobody wants to care.

Nobody has the time to notice.

Sayid was a victim of statistics, they say. Just one more number in a long list that measures in decades.

In 2010, when the book was written, of every ten children born, more than half died before reaching the age of five.

We know it did not get any better. Perhaps never, in our lifetime.

I think of Pampliega’s encounter with the people involved in the renaissance of a bookstore, a cinema, a team of girls playing football, a tireless NGO, the victims turnt into angels of prosthetics and rehabilitation in a hospital and all those hopes and dreams of a dignified life.

I bow to his tribute to the figure of fixers, especially his fixer in Afghanistan, without whose help this book would have never been possible and without whose dedication most of the articles and correspondences around the world would never come to life. If we know anything about a difficult country, we owe it to fixers, not governments.

The people who become heroic in Pampliega’s Testimonio are ordinary people who simply try to do the right thing.

Who choose to stay human and be their better selves whatever context they navigate.

The book made me think of someone I knew, a young Afghan called Mansoor.

People like Mansoor made sense of this world.

He believed in education, he believed in egalitarianism in its purest sense.

He loved children.

When he started working for Save the Children, he followed a special and essential project: bringing clean and safe water to remote villages of Uruzgan province, Afghanistan.

His actions meant everything to so many.

In 2015, Mansoor – just 25 – was kidnapped with four colleagues.

After a month of negotiations, the captors decided to proceed with the slaughter of the five young men.

Along with Mansoor, the captors took the life of Rafiullah Salihzai, 27, Naqibullah Afkar, 29, Mohammad Haroon, 27 and Mohammad Naeem, 24.

All but Mansoor were married and, together, they left 12 children behind.

Mansoor is gone, his killers most likely are still alive.

Antonio Pampliega would have loved him.

They say that when Allah made the rest of the world, He saw that there was left a heap of rubbish, fragments, pieces and remains that did not fit anywhere else. After gathering them, he threw them into the ground and thus created Afghanistan.

Make some sense of it